An auto-ethnographic account about family traditions, food, taste and embodiment. A tribute to my mother and grandmother. Includes recipe of pickled radishes.

An auto-ethnographic account about family traditions, food, taste and embodiment. A tribute to my mother and grandmother. Includes recipe of pickled radishes.

Unpacking Authentic Recipes: Stories of (Re)discovery and Retrieval from Ecuador. By Pilar Egüez Guevara.

As an anthropologist, I’ve spent the past eight years studying the situation of traditional foods in Latin America, especially in my home country, Ecuador. In 2012, I launched a project called “Comidas que Curan” (Foods that Heal) which became a platform for several research projects and food documentaries. Over the years of doing this work, I’ve heard terribly sad, as well as other more hopeful, stories about food and culture, especially from older adults across the country.

While conducting the research for my latest documentary “Raspando Coco” (2018, 30 mins.), an older Afro-Ecuadorian man who has grown coconuts in his farm on the coast for most of his life told me, “the doctors tell us that coconut kills.” He has diabetes and has been told by his doctor to avoid eating coconuts.

Another older Afro-Ecuadorian man who used to sell coconuts for a living at one of the major ports in Esmeraldas—the largest coconut-producing region in the country—told me that he had high blood pressure. In addition to coconuts, the doctors had told him to avoid seafood, plantains, and yuca, all of which are staple foods of the regional cuisine.

Further still, a young teenager who works after school peeling coconuts at a farm for a meager wage, told me he learned at school that coconuts should be avoided because they are high in fat. When I asked them what their favorite foods are, nearly all of the people I interviewed (about 40) said their favorite food is a coconut-based fish or shrimp stew, in Spanish encocao, an iconic traditional dish from this region.

While older adults recall eating coconut in meals almost every day as children, some of them said they now try to limit coconut consumption to once a year. And when they do eat their favorite, culturally meaningful foods, they do so with fear of getting sick, and a side of guilt.

For an earlier documentary project in the coastal region of Manabí, I interviewed older men and women and produced short documentaries of them cooking their favorite traditional foods. This region is known for its dairy farms, and particularly for its unique type of very dry, salty cheese which can only be found there.

Dairy and peanuts are what make Manabí’s cuisine distinctive and recognized as one of the most delicious in the country. Yet, the majority of people I interviewed were very confused as to what I meant by “butter.” When I asked them to list and show me their recipe ingredients, I realized that they said “butter” to actually refer to margarine, a product sold at the grocery store which consists of a blend of refined vegetable oils, some of which are hydrogenated to provide the semi-solid texture of butter, plus some butter flavor and color. I then learned of the widespread belief that vegetable margarine (and oils) are healthier options and that they have been told (by doctors) to avoid real, cow-butter.

This is rather contradictory for Manabí considering that in urban areas like Bahia de Caráquez, milk gets delivered in the mornings straight from the farm to people’s homes in motorbikes. Fresh butter made artisanally from local farms’ pasture-raised cows is habitually made at home and can also be bought by the pound at any food market for a cheaper price than the branded, industrially-produced margarine.

Above: artisanal butter (right) and grated yuca (left). Yuca tortillas in Manabí are traditionally baked in a kind of wood-fire oven which dates from pre-colonial times. Photo credit: Allison Corbett. View the full recipe video.

More recently, I taught online this past June 2020, in partnership with my colleague Javier Carrera from the Seeds Savings Network of Ecuador (Red de Guardianes de Semillas), a grassroots organization advocating for regenerative agriculture and ancestral seeds’ preservation. Our class was titled “Cooking for a Strong Immune System.” We focused on the nutritional value and the immune-boosting function of traditional foods, divided into four broad categories: bone broths; organ and raw meats; fermented/soured/sprouted/soaked foods; and vegetables and fruits.

About 800 people from all over Latin America and other parts of the world signed up for the class, although the majority of participants were Ecuadorian. As we started off the course, several students raised concerns about whether liver from animals was safe to eat because they had heard that the liver is a “filter for toxins”, and had been told to avoid it. One student raised a similar concern about “harmful toxins” in bone broth. Several students commented that doctors had told them that traditional soups made with bone broth have no nutritional value. They claimed they are mostly water with vegetable flavoring since the vegetable nutrients have been destroyed by the heat. Disregard for the value of soups is rather ironic for Ecuador, given that it is a tiny country with one of the greatest variety and quality of soups in the world (only second to China according to a recent report).

Many of the students were pleasantly surprised to learn that traditional fats, like lard and butter, were healthy choices, especially those who work or live close to local farms, yet had been using refined vegetable oils for cooking, per the current medical recommendations. They appreciated us presenting evidence that traditional animal foods, long disregarded and advised against, are in some cases more nutritious than vegetable sources, which is the case of liver—nature’s most concentrated source of Vitamin A.

The excitement over having their culture and local foods validated showed in their posts on the course forum. Some students spontaneously shared pictures of forgotten and rescued grandmothers’ recipe books; others decided to cook their own family’s variations of course recipes; others inquired how to make butter and lard from scratch, and proudly shared pictures of their results with the group. Students thanked us for sharing something more than just recipes to get healthy. We had touched on something deeper as we opened a path to reconnect with their heritage.

Ecuador has a history of shaming people for eating their traditional foods. The now labeled “superfood,” quinua (quinoa in English), is an ancestral food of the Andes that was forbidden during colonial times. Subsequently, up until the 1980’s, quinua was looked down upon as a “food of the Indians”.

In fact, shaming food goes hand-in-hand with shaming the people who eat them. Historically, those people have been low-income, indigenous and African descent groups, marginalized and oppressed under Spanish colonial and post-colonial systems. However, as we are now starting to recognize, their local, heritage-foods were much more nutritious than the alternatives later introduced from the United States through the modern food industry, which continues to be recommended by western medical authorities.

Sadly, shaming and fear of traditional foods are still alive in Ecuador. As I found through my years of research, food prejudices based on obsolete scientific ideas dating from the 1950’s in the United States, continue to turn Ecuadorians away from their locally-produced traditional foods. This is rather tragic since regional cuisines are sources of healthful, local, and widely diverse foods, but more importantly, they are a way to stay connected with our culture. These foods and recipes have been perfected and protected over millennia to give us the safest and most delicious foods, which are also charged with the meanings, experiences, and the sense of who we are and where we come from—our history.

Shame and guilt should not have any place in the experience of eating. They don’t benefit us. They benefit big industries by keeping consumers confused and afraid. They reinforce exclusion and prevent us from loving ourselves and our culture. They also are useless emotions that turn any food into an imaginary threat, creating needless stress that interrupts our ability to adequately assimilate and enjoy food.

The struggle is not just about access to food and transforming our broken food system. It is a collective struggle to dismantle obsolete beliefs that block our access to the knowledge and ability to appreciate our food heritage and enjoy our foods freely, without guilt, and with pride.

This is culinary justice.

Support our work! Buy a licensed DVD of our latest documentary Raspando coco (Scraping coconuts) (2018, 31 mins. Spanish with English and Japanese subtitles) licensed for home/personal viewing or educational use. Stay up to date with our research by subscribing to our newsletter. Watch our previous documentaries on our YouTube channel.

To hear the podcast interview with Diana Rodgers, RD of The Sustainable Dish Podcast, visit this page to download it to your favorite streaming platform.

Pilar Egüez Guevara, PhD is director and founder of Comidas que Curan, an independent education initiative to promote the value of traditional foods through research and film. Her documentary Raspando coco (Scraping coconuts) received several awards and was presented at film festivals in the United States, Europe and Japan. You can find her on instagram.com/raspando_coco and facebook.com/comidasquecuran.com.ec.

This piece was originally published in the Sacred Cow blog on July 2020. Special thanks to Michelle Patiño Flores for her edits and comments on this piece. Thank you to Diana Rodgers, RD for the podcast interview and the guest post invitations.

Hello friends!

I am thrilled to announce the trailer release of our documentary film Raspando Coco /Grating Coconuts. This film is in the making!

Interest in coconut products has only increased since we launched this campaign. In Ecuador, many different brands of coconut oil are out, selling like hot cakes in expensive health markets and supermarket chains, something unprecedented in the country’s history.

Unfortunately, much of this promotion comes with misinformation. This «new» knowledge about coconut’s health benefits is being filtered by popular media narratives and myths about health food products that come from the United States. For instance, an entrepreneur in Esmeraldas, Ecuador recently contacted me. She works to promote coconut oil and other coconut products made by women in the northern part of the province. The oil they are trying to sell is traditionally made by heating the coconut milk (pressed off of grated ripe coconuts) to render the oil. It turns out, this entrepreneur told me, consumers in large cities are turning down their products claiming they will only buy coconut oil that has been «cold pressed.»

This news just made my heart sink. It takes only 5 minutes and a few keywords on Google to learn that it is extremely difficult and highly inneficient to extract coconut or other oil out of its seed without using heat. Centrifugal (mechanical) cold extraction is one very inefficient and method which is not what vendors of so called «cold pressed» and «raw» coconut oil use. U.S. companies invented the term and labeled their products «cold pressed coconut oil» by setting an absolutely arbitrary temperature cap at 50 degrees Celsius (120 Fahrenheit) during the extraction process. Ecuadorian vendors then use these arbitrary standards of U.S. companies to label their product «cold pressed» and «raw» in local markets. The unintended but unfortunate consequence is to drive Esmeraldan producers using traditional techniques tested over centuries, out of the emergent urban markets for coconut oil in major cities in Ecuador. This story illustrates just how urgent our documentary project continues to be very particularly for Esmeraldas–one of the most impoverished regions in the country. The recent popularity of coconut oil in urban areas should be an opportunity for Esmeraldan entrepreneurs to benefit from commercializing their local products.

Watch the trailer and follow us on vimeo for updates on the film’s release!

Thank you for your continued support

¡Salud!

Pilar Egüez Guevara, PhD

I was honored to have been invited to present this lecture at the Anthropology Department of Sonoma State University, on December 4 2015.

In this lecture I will look at:

The world’s population has been growing older particularly rapidly during the past half century. Today for the first time in human history, most people can expect to live into their 60’s and beyond. According to the World Health Organization, between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the world’s population over 60 years will nearly double from 12% to 22%.

Source: World Report on Aging and Health

It used to be that younger generations surpassed the number of older people. However now, and even more so into the coming decades, there will be more older people than children The WHO estimates that by 2020, the number of people aged 60 years and older will outnumber children younger than 5 years.

An evidence of this is that many adults and young adults will have living (rather than dead) parents who live into their 80’s and 90’s, which didn’t happen too often before, when they died at younger ages. Also, more young children will get to know their grandparents and great grandparents, especially their grandmothers, given that women live longer than men.

There are two major reasons behind these ongoing changes. First, over the past century people have been dying a lot less. Medical developments that helped prevent death from infectious diseases such as influenza, pneumonia, and even diarrhea used to take people’s lives at very young ages. Second, women today are giving birth to a lot less children compared to what they did in previous decades. Over time, the consequence of these two factors, lower mortality and lower fertility rates is that gradually older people are outnumbering younger people, so that the proportion of older people is larger than the proportion of younger cohorts in a given population.

For instance: today in Japan, people aged 60 and older are 30% of the population compared to people under 15 years of age who are only 13% of the population.

Source: WorldLifeExpectancy.com

The second consequence is that our lifespans have increased. We are living longer lives since we don’t die as often given our greater access to health services.

For instance a child born in Brazil today can expect to live 20 years longer than the same child born 50 years ago.

What are the implications of living longer lives?

Gains in the human lifespan have been an achievement of our time and our societies. They reflect the advancement in medicine, but also the greater access of medical services and education to a wider number of people.

Life expectancy was used for quite some time by scholars and policy makers, as an indicator of human progress, something that helped us measure how well we are doing as a society. However, at some point people started asking if living longer should be considered a goal in it of itself. If not, what conditions need to be met in order to make the most out of those extra years of life at old age?

The answer is obvious: health. We would need to ensure that we remain in good health in order to take advantage of the opportunity to live extra years of life and start new life projects.

It does not make sense to champion longevity without taking into account the quality of the lives we will live during our extended lifespans.

What common conditions prevent older people from living a quality life at old age?

Living longer is not necessarily good if at the same time disabilities and diseases become more common, as they have in the past decades. For that reason, scholars and policy makers have drawn more attention to the measure of healthy life expectancy, a measure that takes into account disabilities in older age.

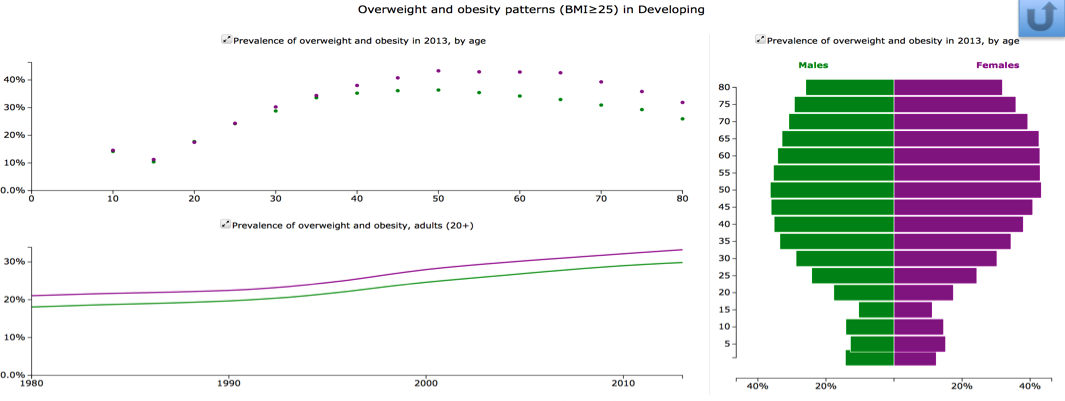

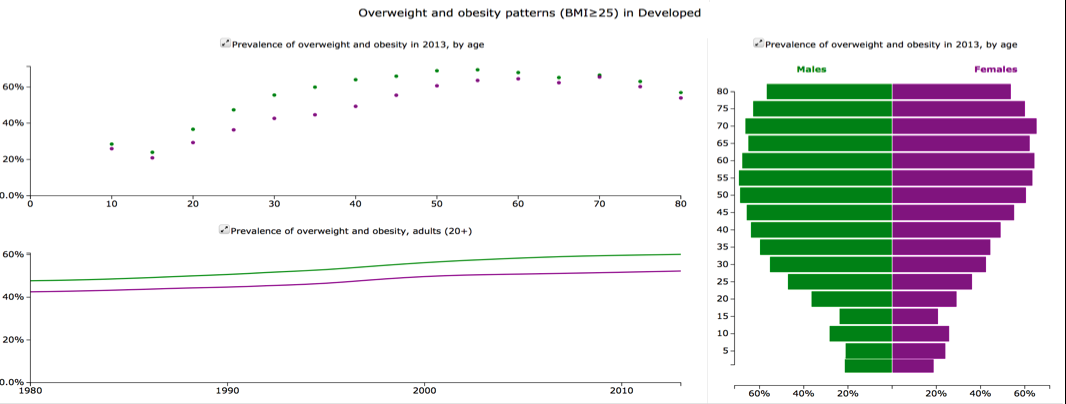

There are major differences in life expectancy across world regions, across countries, as well as between men and women. For instance, the pace at which populations are aging is much faster in developing countries compared to developed countries. For instance, in France the share of people 65 or older doubled in a period of 100 years (from 7% to 14%). However, it will take Brazil and China less than 25 years to reach the same growth in the older adult population.

Similarly, the countries that have gained the most in life expectancy, have also seen more years of life lost to disabilities. In the chart below, the blue-colored bars show chronic diseases, more prevalent in more developed countries. Although red colored bars (indicating infectious disease prevalence) are more frequent among less developed countries, they coexist with growing chronic non communicable diseases in fast-aging developing world. This chart shows that the longer people live the more likely they are to develop disabilities and disease – age is a major determinant of health in older life.

With respect to gender differences in the aging process, women worldwide have longer life expectancies– they live about 7 additional years compared to men. However, they are also more affected by chronic conditions such as diabetes, obesity, arthritis, and ostheoporosis. Women are also are more likely to develop functional disabilities compared to men which makes them dependent on the assistance and care of others to be able to perform everyday activities. As I mentioned earlier, this means that although women live longer lives, they will live more of these additional years of life with chronic conditions and disabilities.

The chart below illustrates the gender disparity in disabiltiy and life expectancy among older adults in Sao Paulo, Brazil between the years 2000 and 2006. At age 60, older women in Brazil can expect to live about 22 additional years of life. Of these additional years, they can expect to live 6 years with disabilities. By contrast, men at the same age of 60 can expect to live about 16 more years, and only about 2.5 of those years with disabilities–less than half of the additional disabled life expectancy compared to women.

The above results beg the question: How can we make sure we age well and with health?

Health at older life depends on genetic factors, personal characteristics such as socio-economic status, gender, ethnicity. It also depends on events and conditions experienced throughout the person’s life course for example lifestyle and behaviors such as diet, exposures to health risks, such as smoking, and the interaction with environments (accessible buildings or environments that encourage physical activity, access to health services, community and family support).

We have little or no control over our genetic endowment or our personal characteristics such as gender, race or ethnicity, or even the socio-economic conditions that we were born into or have to live in given moments of our life. Lifestyle, on the other hand, is something that we can modify more easily. An important part of our lifestyle is our diet.

Over the past century, there have been long term changes or transitions in what we eat which are very much related to the long-term changes in population aging and health that I explained at the beginning. These long term changes in diet are known as the nutrition transition. The nutrition transition goes hand in hand with the growth of cities and the related urban lifestyles that they bring about. For instance in the U.S. the urban and rural populations were about the same in the early 1900’s. Today the majority of the U.S. (about 75%) population lives in cities. In developing countries like Ecuador this change was much more dramatic: while in the 1970’s about 70% of the population was rural, today about the same proportion—70% of Ecuadorians live in cities.

Life in cities is dramatically different from life in the country: it is fast-paced, people are affected by stress and contamination. Also, given time limitations and long distances mean that people do not do exercise regularly, or nearly as much as what people living in rural areas have to.

In this context, and particularly since the early 20th century, many new foods entered our diet. A good example of a relatively new food in our history is Crisco.

Crisco is shortening, a kind of solid fat which is used for baking. Crisco was first marketed as a cheap alternative to pork lard and butter, which were the most common fats people used to cook with in the early 1900s. Crisco is produced in a factory by heating up cottonseed oil or other liquid seed oil like corn or soybean oil at high temperatures in a process called hydrogenation. This process creates a kind of fat molecule that we now know as trans-fat.

Crisco is a good example of the kinds of foods that were gradually introduced in our diets as the industry started to take greater control of our food supply. Since the mid 1900’s our consumption of industrialized foods and ingredients increased dramatically, particularly refined vegetable oils, such as corn oil or soybean oil–these refined oils had never been part of our diet.

Also we started eating high-calory and highly processed refined foods such as refined sugars and carbohydrates in amounts too high compared to what people living in cities, with lower physical activities, really needed.

The sharp rise in obesity, diabetes and heart disease and other chronic, non-communicable diseases over the past 50-60 years, are very much related to these historical lifestyle and dietary changes.

Source: HealthData.org

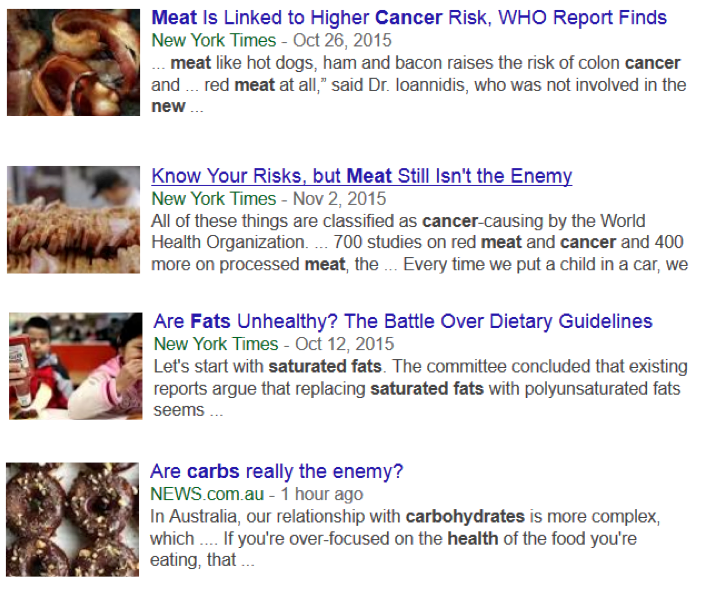

Diet is very malleable, it is something that we can modify more or less easily. For this reason countless studies have examined the associations between what we eat and the risk of developing specific chronic conditions such as heart disease, cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, and many others.

In spite of this, diet and nutrition are also some of the most contested fields of study. The evidence on the relationship between diet and specific health conditions is conflicting and is constantly changing with the advancement of research and the publication of new findings.

For example, the association of different types of fat and heart disease has been a major controversy in the literature and among policy makers over the past few years. Is fat good or bad for you? Scientists have not agreed. This lack of scientific consensus creates a challenge for policy makers and practitioners over how to advise diet and nutrition recommendations to an entire population.

At the same time, the confusion over what to eat has created an opportunity for the industry to sell products such as supplements, foods and diets that accompany claims of having a specific therapeutic effects or cure particular health conditions.

Coming from Latin America, I became interested in diet culture in the U.S., and soon noticed there is a subset of therapeutic diets which have gained popularity here over the past 15 years.

This subset of health diets have a common underlying philosophy: they look for solutions to modern health problems in the ways and the diets our human ancestors ate. I will comment on three of them.

Paleo

The Paleolithic diet posits that we as human beings have not changed much, genetically for about 10,000 years since the Paleolithic era. Therefore, they say, we are meant to eat like our hunter-gatherer Paleolithic ancestors, a diet largely based on meat, vegetables, animal fats and nuts, but very little or no carbohydrates or dairy, which were introduced later with the dawn of agriculture. The Paleo diet has gained many adepts, particularly in the United States and Europe, although it has been highly questioned due to its unscientific claims about what the Paleolithic diet really looked like (for instance, its been shown that Paleolithic peoples did eat grains). With respect to its therapeutic value, Paleo diet has been questioned for not being very effective, but rather quite damaging for women’s health.

Weston Price Foundation

Another popular diet that looks to our ancestors for cues about how to gain health is promoted by an organization called the Weston A. Price Foundation. This organization is named after an American dentist who lived in the 1930’s who traveled the world studying the diets of healthy populations. The WAPF believe that optimal health can be gained by eating the traditional foods and diets of people around the world, particularly indigenous peoples in the Pacific, Africa, the Americas, and Australia. The WAPF are strong advocates of dairy products, notably raw milk and cheese, and animal fats such as lard and butter which they believe are protective against modern diseases like obesity, bone and dental problems, as well as against heart disease. As opposed to Paleo diet advocates who look further back in history, the WAPF have chosen more recent ancestors to imitate: their point of reference of healthy diets is as late as the 1950’s before the massive industrialization of food introduced processed foods into the diet and damaged our health.

Decolonial

One last example I want to comment on are the decolonial or decolonization diets, which have gained ground lately in the U.S. and Canada. Advocates of diet decolonization identify themselves with the broader political movements of indigenous and native peoples in the Americas. For this reason, they have chosen the period before the European conquest as the point of reference of what constitutes an optimal diet for health. For them, to “decolonize” the diet means to eliminate foods introduced during colonization (largely farm raised meats, dairy, eggs and other non-native foods like rice). As a consequence, decolonization diets have made a vegan or vegetarian (meat-less) interpretation of indigenous diets, in spite of the fact that in reality, native peoples of the Americas did eat a wide range of meats and fish. On a deeper level, to “decolonize the diet” means in their words “ to reclaim our cultural inheritance and wean our bodies from sugary drinks, fast food, and donuts. Cooking a pot of beans from scratch is a micro-revolutionary act that honors our ancestors and the generations to come.” (Luz Calvo and Catriona Esquibel Decolonize your Diet). In other words, their particular approach to diet has both therapeutic as well as political claims and motivations.

These three examples show the importance of culture in influencing what diverse groups of people today consider and construct as a diet for optimal health.To some it makes sense to look for cues for diet and optimal health in 10,000 years old prehistoric ancestors living before the dawn of agriculture. Yet to others, it makes sense to resemble more recent ancestors in the 20th century and up to the 1950’s before the dawn of large scale food industrialization. Yet others believe that native American ancestors living before the dawn of European conquest in the 1500’s can offer some cues as to how and what we should eat to gain health.

If we see beyond the politics that influence these perspectives on ancestral diets and health, the reality is that, as I said earlier, for the first time in history, we have ancestors that are not dead, but are still alive today. These are people in their 60s 70s 80s and even 90s who lived through the transitions and transformations in nutrition, population aging, health and disease that I discussed above. For this reason, these people’s testimonies and life histories are a unique opportunity to learn about how major transformations that happened over the course of the 20th century have impacted their lives and their health today.

In a future post, I will explain my motivations to create an ethnographic film and food education project Comidas que Curan to learn and listen to the stories my own living ancestors in Ecuador and Latin America.

Takeaways

World population is aging at fast rate. People are living longer, however the health of older population is not improving. Chronic diseases and disabilities are taking away the opportunity to live these additional years to the fullest potential.

Women fare worse than men in terms of health and life expectancy–-we live longer but with more of these additional years disabilities and chronic diseases compared to men.

Diet and lifestyle are one of many health determinants that can be modified to prevent chronic diseases and related disabilities.

There is controversy over what we should eat for good health. No consensus exists over what constitutes a healthy diet.

Many trendy diets today look to our ancestors’ diets for cues about health. Ancestors and older people become important sources of knowledge about health, diet and healing.

The transitions and transformations in population aging, nutrition and health of the past century provide a unique window of opportunity to learn about diet and health, as do the testimonials of our living ancestors today.

In an era of trendy diets and «superfoods» from around the world, it is hard to believe that those foods could be inaccessible or even rejected by the people who live near or grow them. Here is a summary of the complex story of why people in the tropical regions of Ecuador, where coconut is an ancestral food, have a prejudice against coconut, why they are having less access to it, and what you can do to help make a change.

Esmeraldas (literally “emeralds”) is known Ecuador, a country in South America, as the “green province,” alluding to the lush vegetation of its humid tropical forests. Located on the northern Pacific Coast of Ecuador and bordering with Colombia, Esmeraldas is a region populated mostly by people of African descent. For working class mestizos (mixed race people) from major cities in the highlands, Esmeraldas has always been the number one vacation destination. Esmeraldas’ beaches are a mere 6-7 hours drive from the capital city of Ecuador, Quito. The coastal area highlights the regional cuisine of Esmeraldas, particularly seafood, a major attraction for visiting tourists.

Ecuador has a rich and varied cuisine due to its diverse ecological geography. While a high altitude tuber like the potato makes the food of the highlands distinctive, coconut is the essential ingredient in Esmeraldan cuisine. “Encocado” (literally “coconuted”), the iconic Esmeraldan seafood or meat stew cooked in coconut sauce, sparks the imagination and ignites the taste buds of Ecuadorians. But for black Esmeraldans, encocado is a potent symbol of their identity. It is an essential part of their cultural heritage as an ethnic and regionally distinctive people.

In the old days, Esmeraldans made everything encocado. Older men and women testify to eating coconut in almost every single meal of their day. A typical day could include hot chocolate made with freshly pressed coconut milk and local cocoa bean paste for breakfast, guanta or fish encocado for lunch, and vegetable soup in coconut milk for dinner. Coconut meat pieces with grated panela (evaporated cane juice) made a snack, and masato—ripe sweet plantain, coconut milk and cinnamon smoothie—was a refreshing, energizing drink at any time of day. Grated coconut and panela are the only two ingredients in a still popular traditional desert: “cocadas.” Boiling hand grated and pressed coconut milk with panela and spices made manjar de coco, a thick, sweet coconut treat. Homemade coconut oil was commonly used as a skin and hair conditioner, and medicinally as a laxative. Coconut palms grew on rural farms and in the backyards of anybody’s house. Indeed, coconut was ubiquitous in Esmeraldans’ everyday life 50 years ago, but no longer.

Doña Matilde Angulo taught me how to make masato from scratch at her home in the neighborhood of La Tolita, in Esmeraldas. (Photo by the author)

Doña Matilde Angulo taught me how to make masato from scratch at her home in the neighborhood of La Tolita, in Esmeraldas. (Photo by the author)

Masato—a traditional Esmeraldan drink made with ripe sweet plantain, coconut milk and cinnamon. (Photo by the author)

Habits have changed and new industrialized foods have been introduced in the diet of Ecuadorians, particularly since the 1970’s. However, the dramatic shift away from coconut in Esmeraldans’ diet is likely due to its sharp rise in prices. While in the early 2000’s, one coconut cost as little as 10 to 25 cents, today they are sold for as much as USD $1.50 to $2.50 in times of scarcity. How were coconuts made scarce in the local markets of one of the major coconut producing lands of Ecuador?

Over the past few decades, plagues decimated coconut palms, although that’s not the whole reason for the price hike. Ecuador’s major cities, Quito, Guayaquil, and Cuenca, have become huge markets for coconuts from Esmeraldas for use in a growing food industry, particularly as an ingredient in pastry products and granola. More recently, government programs included granola (with grated coconut from Esmeraldas) as part of school breakfasts in public schools throughout the country. It should be noted that Ecuador did not engage in international trade of coconut before the 1990’s. Demand for coconuts in Ecuador’s urban-centered food industry increased to the point of sustained importation of coconut to Ecuador, especially from Peru, Mexico, Colombia, the Philippines, and the United States. At the same time, Ecuador also started exporting coconut in the early 1990’s, sending most of its produce to Spain, the United States, Colombia, and Argentina.

This high coconut traffic across local borders explains how coconuts from Esmeraldas arrive on the plates of school children in Ecuador’s dry, cold highland towns and cities; or to the passersby in cool-weather Quito who buy coconut juice from the street carts of Esmeraldan vendors; or even to health-conscious, middle class, mestizo and white urbanite consumers of granola and yogurt for breakfast. Internationally, Ecuador’s coconut trade provides additives widely utilized in cosmetics and a grand assortment of health food supplements in the United States and Europe.

This boost in Ecuador’s coconut trade, and its correspondent toll on economic accessibility in Esmeraldas, also explains why Esmeraldans today may substitute the milk from expensive fresh grated coconuts with pasteurized commercial milk to make their encocados (a 1-liter bag is a dollar). And, this is also why the traditional manjar de coco or pan de coco (coconut bread) is now made with plain cow’s milk instead of coconut. Increased trade also helps explain why entrepreneurs of artisanal coconut oil, like Don Julio, were forced out of business after the rise in coconut prices and the introduction of commercial brands of fake, coconut-scented mineral oil. Finally, the boom in local and global coconut demand accounts for why Esmeraldans of today eat coconut foods only a few times a week, and in some extreme cases, only once a year.

It’s been 20 years since Don Julio Prado, a former entrepreneur of coconut oil in the town of Atacames in the province of Esmeraldas made coconut oil.

It’s been 20 years since Don Julio Prado, a former entrepreneur of coconut oil in the town of Atacames in the province of Esmeraldas made coconut oil.

He demonstrated the process upon my special request. See more photos here. (Photo by the author).

However, coconuts also grow in people’s backyards in Esmeraldas, and they are freely available to those who own and work in coconut palm plantations throughout the region. Could it be that Esmeraldans are purposefully not eating them? It turns out medical doctors in Esmeraldas and Ecuador are advising their patients against consuming coconuts invoking the long-ago discredited belief about the supposed adverse effects of saturated fat on heart health. With regards to dietary recommendations, Ecuadorian doctors get their updates from the American Heart Association, often pointing to saturated fat to explain rising rates of obesity and hypertension affecting people in Ecuador.

Sadly, a public health food labeling campaign based on the anti-saturated fat dogma is currently underway in Ecuador. The new “stop-light” food labels required on all packaged products are intended to warn consumers against eating foods high in fat, salt and sugar. Medical authorities particularly target traditional fats like butter, lard and coconut, and vilify Ecuadorian traditional dishes that contain these fats. As a result, there is a culture of guilt for eating traditional foods in Ecuador. In Esmeraldas, it is common to hear doctors blame health problems on people’s preferences for traditional coconut dishes. It is hard to find logic in their reasoning, as coconut consumption is at an all-time low in Esmeraldas due in large part to the increase in prices and the medical campaigns launched against it.

People in Esmeraldas, more than anywhere else in Ecuador, have the right to know the truth about coconut. With access to knowledge, they can reclaim what is in their heritage and reap the benefits from their culturally meaningful foods. This research project was the basis for the documentary Raspando coco. We created Raspando coco as a window for the world, and in particular, Esmeraldans, an opportunity to access current scientific findings and revisit and reconnect with the history of their local foods. We hope Raspando coco empowers Esmeraldans and people around the global tropics where coconuts are part of their cultural and food heritage, to re-discover and embrace their culinary traditions, with the benefits this brings to their sense of belonging, self-worth, health and well-being.

**Update: Raspando coco premiered in 2018, find more information at www.raspandococo.com . This post was published Dec 22 2014, and updated Oct 4 2020.

Pilar Egüez Guevara, Anthropology Ph.D., Research director and co-founder at Comidas que Curan.

https://www.facebook.com/comidasquecuran.com.ec

This research is part of the collaborative education project Comidas que Curan, blending film and ethnography to document and teach about food traditions and transformations in Ecuador and Latin America.

This piece was originally published in the blog of Render: Feminist Food & Culture Quarterly. Thanks to Lisa Knisely for her edits and comments on this piece.

In this classic from the 1940’s, «el bárbaro del ritmo» (the wildman of rhythm), Cuban music legend Benny Moré demands: «¡Devuélveme el coco!» GIVE ME BACK THAT COCONUT!

That’s what we are onto with our Indiegogo #cocofilm project campaign: lets give back coconut to those who own its rich culinary traditions in Esmeraldas (Ecuador) who are unaware of the benefits of this local and ancestral food. Lets make a film to disseminate up to date scientific information about coconut and health, and of its rich culinary history in Esmeraldas and other parts of the global tropics. Esmeraldans deserve it. They own coconut traditions.

Esmeraldas is a coastal province of Ecuador where coconut has been a staple for people of African descent for centuries. Recently, the traditional uses and health benefits of coconut have made it to the forefront of cutting edge medical research and are being promoted through all sorts of health food and beauty products by U.S. and European companies. There are about 50 brands of coconut oil being sold through Amazon.com advertising it as a health food with all sorts of miraculous properties. U.S. Americans and Europeans have slowly but surely overcome the anti-saturated fat bias, which was based on flawed scientific studies dating to the 1950’s. Saturated fat is an important component in the meaty part of mature coconuts. Science finally caught up with centuries-old coconut-rich culinary traditions in the global tropics. Coconut fat is good, not bad for us.

But as coconut is becoming mainstream in the U.S., it is simultaneously becoming inaccessible to people in Esmeraldas. Although in Esmeraldas coconuts grow in people’s backyards and nearby plantations, people are having less access to it due rising prices (as much as $2.50 per coconut) and outdated medical advice which demonizes saturated fat. Medical doctors in Ecuador are not up to date with the science, and Esmeraldas’ rich coconut traditions are being unfairly demonized.

If you are into coconut oil, oil pulling, coconut for hair/skin care, coconut oil for cooking and baking, and into a health-conscious life in general, this is your chance to show that you also care for the health of the people who grow your food.

If you spend a fraction of your coconut oil or health supplement purchases donating to make this important film a reality, you can make the world of a difference in the lives of those who grow coconuts in their backyards and yet don’t care to use them under false beliefs that deny their wise traditions.

Do you love coconut? Help us by liking our project facebook page Comidas que curan, and by sharing and donating any amount in our Indiegogo campaign page.

Click here to read the full story and donate for this important cause!

http://igg.me/at/cocofilm/x/8973993

If you still haven’t, watch & share our #cocofilm campaign promo video/ trailer and get on grooving to the sweet tunes of coconut, in this case all the way from Esmeraldas, a famous tune played on Marimba (Andarele) by Don Naza y su Grupo Bambuco.

Our indiegogo crowdfunding campaign is almost ready to be launched!

Over the past two years I have been researching and learning about the traditional uses and health benefits of coconut which is a traditional food of Esmeraldas, a province of Ecuador. In Esmeraldas, coconut has been a staple for people of African descent for centuries. However coconut has now become inaccessible to people there due to high prices and outdated medical advice which demonizes saturated fat.

I will be sharing the link to the indiegogo campaign site soon. Meanwhile, you can help build momentum by reading and sharing an article I wrote about coconut gentrification in Esmeraldas, sharing and watching a video of my talk at the Ancestral Health Symposium in Berkeley, and liking my project facebook page Comidas que curan.

Do you love coconut? Share now and help support this project!

Meanwhile, lets coconut groove with Arturo Sandoval. Happy Monday!

During the summer of 2014, I taught a course on the Anthropology of food and ethnographic documentary to community members of all ages and U.S. study abroad students in Bahía de Caráquez, Ecuador. This seminar is taught as part of the summer programs offered by La Poderosa Media Project. Check out the video about the course!